| Главная » Статьи » Материалы на английском языке » Зарубежные печатные издания |

Cruise at the Crossroads

Автор: TRIP GABRIEL

Uh-oh. I've ticked him off. The hazel eyes that were gracious moments ago are now as impenetrable as cloudy water, and his wide-set cheekbones seem to be widening even more, stretching the skin taut like a pearly mask. The steel that has suddenly hardened his voice is a surprise, though maybe it shouldn't be, since surely in the Tom Cruise screen persona there is that upfront cockiness, a premonition of violence. It was just this quality that director Oliver Stone wanted in casting Cruise as a paraplegic Vietnam veteran in the new film Born on the Fourth of July. "His aggressivity is what impressed me," Stone says. "I wanted to take his top-dog strength and turn it on its side, to flip it. It's like Top Gun goes to war. You're number one, you're Mickey Mantle, but what happens when you get blown out of the cockpit?" It was while discussing Born on the Fourth of July that I quite inadvertently pissed off Cruise. The conversation was flowing along just fine, everything going smoothly, in a sunny hamburger restaurant in West L.A., when — Blammo! — he blew me out of the cockpit. In the film, Cruise plays real-life vet Ron Kovic, who goes to war as a patriotic marine in 1967 and comes back in a wheelchair, eventually becoming an impassioned antiwar activist. Despite the involvement of Stone as director and co-writer, this is not Platoon II. Most of the film takes place following Kovic's return, when his disillusionment with his country and his useless, pitiful body boils up. He rails against the war makers, the Catholic church and, most dramatically, his rigid Silent Majority parents, whose withholding of approval when he was a teenager made him think he could prove his manhood by going to war. In a climactic scene, Kovic drunkenly confronts his mother with the fact that now, due to a smashed spinal cord, he has no manhood at all. It's just "me and this dead penis," he cries. His prudish mother is shocked. "Don't say penis in this house!" she shouts. "Penis, penis, penis!" yells Kovic, sick of all the hypocrisy he sees. "Big fucking erect penis!" This is powerful stuff, and Cruise deeply inhabits the role, giving the most ambitious performance of his career and an utterly convincing one. He spares none of the gritty reality in depicting the indignities of the wheelchair-bound. In one scene he has violently yanked loose his catheter and sits besotted in his own urine. It is not a pretty picture, and it's a long way from the sexually magnetic, rambunctiously physical roles in which Cruise became a star. Before the film's trailer came out, Universal Pictures fought a raging battle with Cruise's people to prevent them from releasing stills of Cruise in a wheelchair, for fear of turning off the audience. The studio was concerned about whether the picture would attract the folks who've flocked to Tom Cruise in the past — the guys who find him manly and rebellious, the girls who find him vulnerable and gorgeous, the high-school seniors across the country who in 1988 voted him "Top Hero of Young America." In a word, would these folks come to see Tom Cruise as a guy without a male member? I ask Cruise whether he had any doubts about accepting the part: "Did you think how your traditional audience might respond to the role?" "No, I didn't," Cruise says. "What do you mean, 'traditional audience'?" The audience that on the strength of his name alone made Cocktail, in which he played a "star bartender," a $70 million success despite bad reviews, including some calling it Cruise's first flop. "The audience that will see almost anything if they think they're going to get a character like that from you," I say. "Like what?" Cruise demands, an edge in his voice. He rarely cuts you any slack in conversation. He'll pick up an unexamined thought and toss it back at you. "A character who's young, healthy, robust," I say. "With sex appeal. You know, in just the most stereotypical terms ... your image as a film character." There follows a long pause in which Cruise seems to be doing a slow burn. Finally, he says, "You're the type of person who stereotypes things. That's not the way I think. I have to disagree with you in that. Just the opposite. If you look at the films, there's a range...." And he makes the point that actors who stop taking risks and gambling on new roles grow stale. Yet the irreducible reality is that there are very few actors whom audiences will accept in any role. The cable channels are gorged with product that moviegoers would not buy from stars they thought they knew. "That has to be a concern," I say. "Why?" Cruise asks. "From what point of view?" "I suppose from the point of view of wanting to continue to work successfully and have some clout in the business," I answer. There is a very long pause. "Let me tell you something," Cruise begins, the sarcasm dripping. This is when it's clear I have pissed him off. "I don't know how many times I have to say this, but having clout in the business has never been a huge concern of mine. And that I have never done a film for money. And that, that ..." He sputters to a halt. "I don't know what else to say." Really, there is nothing else to say. It can be documented that Cruise, who has emerged as the most powerful young actor in Hollywood, has other things on his mind than his fee, which is now about $9 million per film. According to Don Simpson, who coproduced Top Gun, the number-one-grossing movie of 1986, Cruise could have commanded five times as much for a sequel but wasn't interested. To make Born on the Fourth of July, he agreed to work for scale and invest a year of his life on the gamble that the film would make money and pay him back later in profit participation. "Not taking money to do this picture is smart," says Oliver Stone. "A lot of people would not do that. A year of work, and what if the picture does nothing? I think Tom's Wholly obsessed with being an original. He's going to take it out to the edge as far as his persona and soul will allow." And what of that persona? My question — will his traditional fans be open to him in a role that denies his good looks and explosive energy? — seems innocuous enough. But Cruise responds by undercutting the question, denying the premise, hacking away at my supposition. This, one learns, is fairly typical Cruise behavior. When something doesn't register right — words, a tone of voice, a situation — he confronts it head-on. A dyslexic, Cruise never went to college and doesn't express himself easily in language; but on the other hand, he seems incapable of disguising his thoughts behind a smoke screen of words. He speaks slowly, sometimes guardedly, sometimes with searing directness. He wants to know exactly who he's dealing with. In the hours we spend together, he does almost as much interviewing of me as I do of him. He is full frontal, this Cruise. He gets in your face. When Cruise speaks of his career, he's likely to call himself an "actor-artist." It sounds like he doesn't quite want to say he's an artist — that would be too pretentious — but at the same time, he's more than just an actor. Certainly his choice of roles in the last few years has shown his hunger to do serious "actor-artist" work. And some of the most respected names in the business have had faith in him. When Martin Scorsese and Paul Newman were casting Newman's sidekick in The Color of Money, says Newman, they never seriously considered anyone but Cruise. Dustin Hoffman spent two years developing Rain Man with him. And Oliver Stone, who made his reputation with films that didn't need stars, held up the start of Born on the Fourth of July for nine months waiting for Cruise. With Born, Cruise for the first time carries the full weight of a dramatic picture with a Big Theme, a movie much anticipated in Hollywood, which has already started the drumbeat for an Academy Award nomination. Looking back, it almost seems like he planned it this way — first costar with Newman, then costar with Hoffman, then step out on his own. He appears to have served a self-assigned apprenticeship with two of the great ones. "Absolutely right, that's how I felt," he says. Cruise is on the road to being some combination of Newman and Hoffman, with the gifts of both actors. He has Newman's sincerity and Hoffman's ability to mime — to mimic exactly a character's inventory of physical gestures. Cruise holds up Newman as the very model of how an actor should build a career and construct something stout and watertight that'll last for decades. "I want to go all the way," Cruise says. "Look at Newman, look at what this man has created as an actor and a human being." Cruise took a giant step toward longevity by working with Hoffman on Rain Man. Most of the river of praise for this film lapped at Hoffman's feet; his Oscar-winning portrayal of an autistic savant transfixed audiences as they might have been mesmerized by a real autistic with the ability to spout pages from the telephone book. But it was Cruise who made the film work. As an audience, we could not identify with Hoffman's Raymond Babbitt, who was unable to express emotion or truly change. We were forced to identify with Cruise as Raymond's brother Charlie, the recognizably human character. His callousness toward Raymond was a heightened representation of our own fascination and horror, and as he changed to become more emotionally involved, we, too, developed more compassion. The role, says Cruise, "was an accumulation of everything I'd learned. To have worked with Newman and to have such a great role like Charlie — yeah, absolutely, it was exciting as hell." I ask if he could have played Charlie three years earlier, immediately after Top Gun. "It wouldn't have been the same performance," he says. How would it have been different? At long pause. "I'd like to say I've lived a lot of life in those three years to be able to play the role." One thing that happened was Cruise's 1987 marriage to actress Mimi Rogers, who is six years his senior. The two are always on the sets of each other's movies. When I met Cruise, he was planning to be in Salt Lake City for the weekend while Mimi worked on her next project, Michael Cimino's Desperate Hours. ("I'm going to take care of a lot of reading while I'm there," he says.) Correspondingly, she was with him throughout the making of Rain Man and Born. "I wouldn't have been able to make it through Born, I don't think, without her being there," he says. "There were times I was so physically exhausted, and the stuff was very emotional." Oddly, that very week, the supermarket tabloids later claimed, Cruise was living apart from his wife because she threw him out of their Los Angeles house. But he did not sound like a man who had fallen out of love with his wife. On the contrary. "I couldn't imagine being without her or being alone," he told me. I wondered if before they met — Cruise was twenty-three and had been linked publicly only with Rebecca De Mornay, his costar in Risky Business — he had ever been in love. "Uh, not really," Cruise says candidly. "Really?" "There were girls you like a lot," he says. "But I'd never been in love before. Since I've been with her, it's opened me up a lot. I think it's helped me be a better actor. We live a lot of life together. We share everything. That's the best thing about life. Otherwise you go through it pretty sad and lonely and angry." Does that describe the person he was before he got married? "I was pretty lonely, yeah," Cruise says. "I was really lonely before I met her." I ask what means the most to him about his relationship with Mimi. Cruise grimaces. "What means the most?" he says, slipping into sarcasm, batting the question back at me as if he were spiking a volleyball. "Jesus, what's my favorite color?" He's right, though. It's an overly simplistic query. Eventually, Cruise says, "I care about my wife more than anything in the world. She's my best friend. I just really like being with her, you know? I love her." For years he told people he couldn't see himself married. It traced back to having witnessed his own parents' failure with the institution. "You know, coming from a broken home — it did seem like a broken home, my parents got divorced — my worries were 'Jesus, am I going to be faithful? Does marriage work as a concept?'" he says. "I really never thought it could." If Cruise is more open today, more flexible as a personality, the role he had in Rain Man must have struck him as an earlier version of himself. Alongside the autistic brother that Hoffman played — who could not bear eye contact — Cruise portrayed a character he describes as "a spiritual autistic." His Charlie Babbitt had the ability to function in the real world, unlike his institutionalized brother, but in many ways he was just as emotionally boxed off from others. In creating this role, says Cruise, it was painful to confront the part of himself that in many ways seems the essence of his screen persona: edgy, coolly distant, pugilistic. I ask him just how well he understood Charlie Babbitt's experience of being emotionally frozen. "Emotionally frozen?" Cruise says. "Yeah, I felt that way. I felt it in my work as an actor. I felt it just as a person. As I said, before I got married, there were certain things that were hard to face."

Racing appeals to every aspect of the Cruise persona. There's intense competition: "It's a fine line between beating a guy at his own game and ending up in the wall." There's the chance to exercise control over imminent chaos: "I like the sense of a piece of machinery being manipulated down a track at a high rate of speed." And there's solitude, a man alone with his thoughts and feelings and no one he must share them with: "It's calming, you know? I'm in a world of my own. I just feel really relaxed." In the past year, Cruise has iced his own racing to spend a lot of time on the big-league stock-car circuit, soaking it all up for his next movie, Days of Thunder, in which he'll play a brilliant young driver with a hell-raising streak that threatens his own destruction. The idea for the film originated with Cruise himself, who brought it to Top Gun producers Jerry Bruckheimer and Don Simpson. Simpson, who attended a race-driving school with Cruise just after Top Gun came out, has seen his star's obsession with speed close up. "I have been in a car with Tom in Rome, in San Francisco, in Los Angeles, and each time he was in the driver's seat and I was truly scared," says Simpson. "This is a man who is comfortable taking major risks. He likes to be out there on the edge, whether it's in a car or on the screen." Cruise zips the little Honda in and out of the traffic on Sunset, forcing up the rpm's, driving hard even though the car's just an automatic. This afternoon he feels like playing some basketball. We pull into a junior high school, and in the parking lot Cruise changes from street shoes to white high-top Reeboks. He says his fame has never hindered him from going where he pleases. Though he is constantly being recognized, he doesn't habitually wear sunglasses. Nor does he go out of his way to attract attention. He just doesn't seem to think about it very much. In fact, he's so normal looking in person that it would be easy to miss him. Today he's wearing jeans and a gray T-shirt; he has a normal-guy haircut, slightly crooked teeth and even a normal-guy pimple popping up on the right side of his mouth. The school's outdoor basketball courts are empty and surrounded by a locked chain-link fence. A sign says, Authorized Vehicles and Persons Only. Cruise doesn't even see it. He grabs two fistfuls of chain-link fence and pulls himself over the barrier. Just a normal-guy delinquent breaking into a schoolyard. I toss the ball over and climb up after him. We're the only two hoopsters on a big patch of pavement with a dozen metal backboards. Cruise apologizes, saying he's not very good, but it doesn't matter, because he's a scrappy player, chasing the rebounds and aiming one jump shot after another. That's how it was with him and sports in high school. He went out for a bunch of teams, including ice hockey and wrestling, and though he was never exceptional at anything, he was hyperenergetic. It's easy to imagine coaches' wanting a player like Cruise, someone who's aggressive, who's driven to be number one, who's in your face. "It was like running," Cruise says of his feelings during his high-school years. "Nothing was quick enough, nothing moved fast enough in terms of life for me. We always traveled a lot. I still like moving around; I don't like staying in one place. That's why I like racing — it's constantly moving on each weekend." Cruise's teenage years are an emotional well from which he seems to draw even today. That time has shaped his personal mythology, and memories of a difficult, often lonely adolescence regularly enter the conversation. His parents divorced when he was twelve, and the horrible vertigo and insecurity were worsened by his mother's slide into the lower middle class. To ease the financial burden, Cruise spent his freshman year of high school on scholarship in a Catholic seminary in Cincinnati. "More than anything, it had to do with the fact that our family didn't have enough money to feed me," he says, dribbling the basketball. "When you're a kid, you really feel the pressure to lighten it up." As for sticking with the seminary and becoming a priest, Cruise never gave it a serious thought. The idea of being celibate — nooo way. "Even at that age, I was too interested in ladies," he says. "There was a time there when my older sisters and their friends were just starting to kiss boys. They needed somebody to practice on. I'd sprint home from school, go in the bathroom, and they'd put me on the bathroom sink, and my sisters' two friends would take turns kissing me. They taught me how to French kiss when I was eight years old. The first time I almost suffocated. I was holding my breath." Cruise has three sisters, no brothers, and after the divorce he was the sole man around. "I grew up around women, you know? I feel real comfortable around them." His mom moved her little brood often. Cruise attended three high schools in four years. Thus did he live out the nightmare of the self-conscious adolescent: always the new kid in class, always looking for acceptance from a new gang of kids. Those kids, of course, were already deployed in their tight little cliques, and they weren't interested in seeing the new kid for who he was. They just wanted to size him up fast: Was he a jock, a duster, a dweeb? "Sometimes it was frustrating never to be able to break through the social barriers of people's existence," Cruise says, lining up a free throw. "If someone was new or different, it was just brutal." Cruise didn't make many friends as a teenager. He was withdrawn and a bit lonely and not given to expressing his feelings. "Traveling the way I did, you're closed off a lot from people," Cruise once said. "I didn't express a lot to people where I moved.... I never really seemed to fit in anywhere." He was a young man in a hurry, busting to get out. He made the great escape from Glen Ridge High School, in New Jersey — skipped his graduation, in fact — and fled to New York to begin an acting career. There things worked out almost from the start. Alas, the shock was that the real world could be pretty much like high school. People are just as eager to slap a label on you as an actor. "You think at some time you'll outlive that and it will be different, and it's a constant, ongoing thing to try to have people understand you," Cruise says. "People want to put you here, put you there." So that's it. That's what it was back in the sunny hamburger restaurant, when I brought up Cruise's trademark screen image, his "traditional audience," and he grew unaccountably touchy. The fires had been smoldering since adolescence. "That's why you freaked out when I started to stereotype you," I say. "People want to limit things," Cruise says with feeling. "They say, 'God, you're going to lose everything, aren't you afraid?' This may be a hard thing to believe, but I don't give a shit. I don't care. That doesn't mean I'll go out and do anything, but it has nothing to do with me wanting power or me wanting money. It's not that I don't want money, but I never expected to have money, and I don't need a lot. That's not what acting is for me. I love doing it, and I want to try different things. "Maybe from the outside you don't see the changes or what I'm playing with. And that's fine, because I do. I know where my faults are. Somewhere I guess you want to find out, how far can I fall? How deep is the well? When am I going to hit? I want to feel that; I want to know that. How far can I take this? When it's all said and done, I want to be able to look back and say I've pushed it as far as I could. I've made some damn big mistakes, and I look like an asshole a lot of the time. But I did some good stuff, too." Cruise has made far fewer mistakes than most actors. There is one that comes to mind, however — the sickly sweet concoction that was Cocktail. After listening to him speak with genuine passion about wanting to push and stretch himself as an actor, it's hard to fathom how he could have become involved in that daft vehicle, which seemed to function largely as a showcase for his megawatt grin. I ask what went wrong. "What were some of the mistakes of that one?" he says, with a good-natured laugh. "Those are some of my secret pains." We have moved off the basketball court and settled on a grassy soccer field, where Cruise is perched on top of the basketball. He's reticent about Cocktail. Other people were involved. He is nothing if not gracious and can't bring himself to be indiscreet. One of the problems was that the film's milieu was just ridiculous. Supposedly a slice of hip Manhattan, Cocktail was filled with clubs and clientele that looked as if they belonged in a shopping mall in Dubuque, Iowa. "I know, I know, man," Cruise says. "What can you say is wrong with the film? I never believed I was in New York. It just was not the night scene in New York." He laughs with nervous embarrassment at the memory of a screening he watched with Mimi. "You sit there and you go, 'What the hell happened?'" he says. "When we saw it on the screen, we go, 'What the fuck is that? What the hell was that?'" Yet the project started off with the best of intentions. The idea was to make "an interesting little art film," Cruise says. Director Roger Donaldson was coming off the critical success of No Way Out, and Jeffrey Katzenberg, the head of Disney, which paid for it, expected to make an updated version of The Graduate. So Cruise didn't make the picture for exploitation purposes? "Listen, the film was not exploitive," Cruise says. "Halloween 5 is exploitive. The film meant well. You know?" And he cracks up. Wearily, he adds, "I can't even sit here and say to you how many things I felt I did wrong or what happened, because we could sit here for three days and talk." The hell of it is, the film still made demands on him as an actor. It's a shame not to see that effort up on the screen. "It's painful as hell," Cruise says. "You don't work less hard. I mean, I worked my ass off on that movie. It knocks you, and you learn. But that's the thing. You've got to say, 'Let's go, get off your ass and get out there and try it again.'" Cruise is a self-described "shooter," a guy who likes to work nonstop, to jump from one project to the next without a lot of second thoughts and searching reappraisals. He has cracked off twelve pictures in his relatively short career. Each was as fully ambitious a work as he felt capable of at the time. No one can deny that his latest, Born on the Fourth of July, is a serious actor-artist's movie. Cruise is surprisingly good, as convincing in the small details as in the large emotional truths. To play the role, he plunged into the grim realities of paraplegia, visiting hospital wards, wheeling around West L.A. with Ron Kovic, even learning to get into bed at night from a wheelchair. He says he wanted the part as soon as he read the script, which originally had been written in 1978 by Kovic and Stone, based on Kovic's National Book Award-winning autobiography. Back then, Al Pacino was cast in the lead, but the plug was pulled three days before filming was to commence. "Oliver Stone promised if he ever broke through," says Kovic, "if he ever got the opportunity to direct, he would come back for me. He said it was like an old marker for him." Soon after the phenomenal success of Platoon in 1987, Stone called Kovic and told him the time was right — they were back in business. Cruise, who was born on the third of July in 1962, has no real memories of the living-room war nor of the way it radically divided the country, with longhaired freaks lining up on Independence Day to flip the finger at veterans wearing Bomb Hanoi buttons. The film re-creates the polarization of that era in gripping detail. Indeed, for those who were young and impassioned during those years and have since found themselves straining to remember why such a fuss was made in the late Sixties, the experience of the film is like entering a time machine. Cruise himself is a child of the mid-Seventies post-vietnam amnesia. "I remember arguing with kids on the playground about who won the war," he says. "Kids said, 'Oh, we won Vietnam, we're America.' In school we were not learning anything about it." Cruise became seized by a desire to portray the intensity of the experiences that an older generation had had during the Vietnam era. "I never told Oliver this," he says, "but I thought it was almost his life story, too, his Coming Home." Both Stone and Kovic, who had met separately with Sean Penn and Charlie Sheen to discuss the role, felt Cruise had the deepest affinity for the lead character. He and Kovic shared working-class backgrounds, Catholicism, even high-school wrestling. The first time they met, at Kovic's Redondo Beach home, Cruise ran up the driveway and hugged him. "I had my doubts before he came that day," says Kovic. "I wondered if he had the depth to portray me. We had a meeting in my kitchen for several hours, and Tom explained that he really wanted to do this, and he was not going to let me down. I was looking at him, saying to myself, 'He's so full of life. He's so sure. He's so representative of America before the war.' I was thinking, "He's about to go through this hell, and he doesn't even know it.' I was convinced he wouldn't be the same when he came out of this." To hear the star and director tell it, the making of this picture was a small military campaign in itself, a sixty-four-day siege. Stone says Cruise "was on edge every day. He was out there. It was very tough for him physically and emotionally." Cruise calls it the biggest gamble of his career and also his most important role. I asked Stone which scenes were the toughest for Cruise. "The toughest?" the director says. "Everything was tough as far as I was concerned. Having fights with your mother. Having a fight with your brother. A fight in a bar with all this smoke. Getting physically thrown out of your chair at the Republican convention at three on some freezing morning and being dragged along sidewalks, yelling at the top of your lungs. It was all exhausting." If Cruise's role was a piece of risky business, he did not appear anxious or unsure on the set. On the contrary, before a big scene he would be skipping rope like a prizefighter. Then he'd yell, "Let's rock and roll!" and run onto the set. Cast and crew moved from the United States to the Philippines to shoot the Vietnam scenes. After the combat sequences were wrapped, the very next day the schedule called for a scene that in the movie takes place in a Mexican resort, a kind of Margaritaville for paraplegics. Kovic, who went to Vietnam a virgin and returned paralyzed from the middle of the chest down, spends the first night of his life with a woman, a Mexican prostitute. For Cruise, this love scene was the most demanding of the entire shoot. He felt drained after filming the battle sequences, and there was the touchiness of the subject matter. "He's a very shy boy," says Stone. "And he had to do several scenes with whores. It was tough for him." Cruise had spent time with paraplegics and discovered that they can have active sex lives even if they don't climax in a conventional sense. He discusses this frankly and with sensitivity. He recalls that several takes of him with the hooker were tried but rejected. After having played Kovic in a wheelchair on the set in Dallas, he was having difficulty getting into character again as a paraplegic. "I was going at it, and it wasn't working," he says. "I'd nailed the character in Dallas, and then we'd done Vietnam, and then I had a scene where I had to be Ron in a wheelchair again. I was just like, 'I don't know where I am. I lost it. Am I Kovic now?' I remember I was so physically exhausted. I said, 'Oliver, I'm sorry, man, I just don't have it. I'm lost.' He said, 'You are Kovic, just do it, don't think about it.' " They tried it one more time. "I always just saw the scene," Cruise says. "I mean, you can't act all the complexities: 'I'll never feel the inside of a woman. I can feel the pressure of her body, but I'll never feel her skin against my chest. I'll never really.' That whole thing. And also the beauty of this woman, holding a naked woman for the first time and how incredible that is." In his performance, Cruise was building toward some kind of climax. Unexpectedly, tears started flowing down his cheeks. "I remember doing the scene and just letting go, and that's when I started crying," he says. "That wasn't written in the script. That's when we got the whole thing. Paraplegics talk about almost an emotional orgasm that they feel." That's what Cruise got, a grace note as an actor with all the immediacy of a sexual climax.

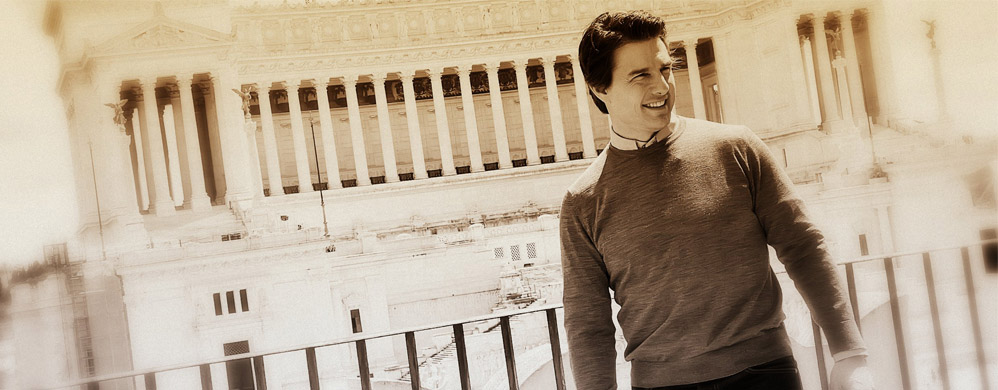

After Born finished shooting, Stone and Cruise both traveled through Southeast Asia, their paths crossing in Bangkok. "You've done a great job, Tom," Stone said one night when he ran into Tom and Mimi. "You should go out and just be young and enjoy the autumn of your youth. Because it's gonna go. Go out now and have a fucking ball." "You're right," Cruise said. And he did unwind a bit, taking time off to travel in Europe with Mimi. But pretty soon he was back in the driver's seat, charging hard into his next project, the stock-car-racing movie, due out this summer. He is charging hard right this minute as he fights the end-of-day traffic on Sunset, racing to return me to my own car. We are now on easy terms, talking excitedly about lightweight subjects, and I don't pay attention to where he's driving. He swings up to a hotel, thinking it's where I'm parked, but it's the wrong place. My car is a good fifteen minutes in the opposite direction. Cruise is already several minutes late for a six o'clock meeting, so I volunteer to jump out and catch a cab. Forget it, he says. He'll return me to my car. "Let's rock and roll!" he shouts and roars back into the rush-hour traffic. Источник | |

| Просмотров: 613 | Рейтинг: 5.0/1 |

| Всего комментариев: 0 | |

The growing pains and pleasures of Hollywood's top dog

The growing pains and pleasures of Hollywood's top dog