| Главная » Статьи » Материалы на английском языке » Зарубежные печатные издания |

On Thunder Road with Tom Cruise

Автор: JEFFREY RESSNER

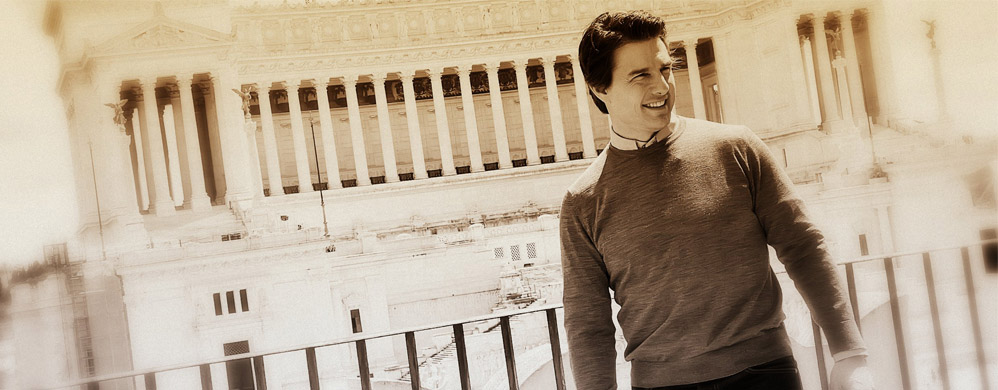

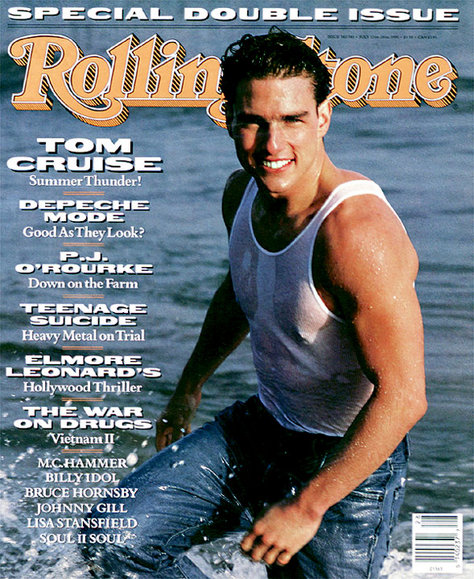

It's Saturday morning, and Tom Cruise is in the back booth of a kitschy Fifties-style diner on Los Angeles's Melrose Avenue, picking at a plate of scrambled eggs and whole-wheat toast. Waitresses appear with coffee refills every thirty seconds to get a closer look. Other customers crane their necks to make sure it's really him. The slightly tousled hair, the boyish features and the white-toothed grin confirm suspicions. The back room is starting to fill up. But even a baby crying in the booth behind him and a busboy loudly chipping a bucket of ice nearby fail to unnerve Cruise. Memory jogged and eyes opened wide, the actor explains why he decided to make his new movie, Days of Thunder, which is about the daredevils who compete in Winston Cup stock-car racing. "I'll tell you when the idea came to me, the exact day," he says. It was four years ago, and he was going around in circles. Literally. Cruise was driving around the D-shaped racetrack at Daytona International Speedway, home of the annual Daytona 500, where he and his racing mentor, Paul Newman, had come to flex some machismo after finishing The Color of Money. Cruise toyed with the notion of a racing movie early that morning while he talked to the drivers and crews at the Florida track. Once he got into a car and started pushing hard on the accelerator, he was convinced. He enjoyed mastering the heavy machine. Roaring down the straightaway while slung low over the asphalt, Cruise felt as if he had entered a different dimension. His vision became clearer and sharper, though every time he blinked, another hundred yards flashed by. And when his car sailed into the sharply banked turns, the G-forces made his head feel like it weighed a ton. In the past, Cruise had driven Porsches and Nissans with Newman. And he once took a souped-up stock car for a drive in Atlanta. But this time something was different. Meeting Daytona's crews and whipping around the trioval track with its steep curves made an especially powerful impression. Climbing out of the car, he exclaimed, "I'm going to make a movie about this!" Four years after that panavision fepiphany in Daytona, Tom Cruise's longtime pet project is opening at 2000 theaters nationwide — just in time for the lucrative Fourth of July weekend. In all likelihood, the picture will rake in millions for its major players: Paramount Pictures, producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer and the twenty-seven-year-old Cruise, who not only stars in the film — for a reported $9 million — but also shares story credit with screenwriter Robert Towne. Insiders claim that Thunder is merely another high-concept summer picture with topspin: "Top Gun on wheels" is the going put-down. In some respects, they're right. Top Gun, a navy-flyboy epic that grossed $176 million, was the box-office bonanza of 1986. Thunder is a similar package. Lots of hardware. The same studio, star, director and producers. On the set of Thunder, crew members even wore TOP CAR caps that mocked the incestuous relationship between the films. Cruise brushes off the comparisons. "There are people who like to classify things," he says, "people who can't see things for what they really are." Cruise sees Thunder in simple terms: a film set against the backdrop of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) circuit that focuses on a rookie driver, Cole Trickle (Cruise), who is forced to reexamine his life and his values after surviving a near-fatal car crash. Behind the scenes, Thunder seems more complicated. The development process alone exhausted three screenwriters. Production costs shot past a reported $55 million. A five-month shooting schedule was marked by weather delays and dangerous stunt work. Perhaps most daunting, a shortened postproduction period forced editors and sound technicians to scurry to complete the movie so it could open just six weeks after principal photography wrapped. A month before Thunder's debut, offices on the Paramount Pictures back lot hum with round-the-clock activity. The time squeeze is especially hard on the editors, who are working to hack 240 hours down to the film's final length of just under two hours. "The only way we can get this finished," says Billy Weber, the chief film cutter, as he tosses back his graying ponytail and hunches over an editing table, "is if we treat every day as a week." A different kind of drama takes place across the studio on sound stage 17. Director Tony Scott is filming a pivotal new scene between Cruise and actress Nicole Kidman, Cruise's offscreen girlfriend, that will preface the movie's climactic race. Trickle is gearing up for his ultimate confrontation on the track, but he's nearly undone by self-doubt. His doctor and lover, Claire Lewicki (Kidman), helps him confront his fears. It is a moment when -- as Simpson fondly proclaims -- the main character learns "the difference between bravery and courage." Cast members and crew began setting up the scene early in the day. By late afternoon, they're still not finished. When Scott insists on doing additional work on the scene, he calls Bruckheimer and Simpson, who are conducting an interview in their office. The producers make no secret of their unhappiness over this turn of events. "Jerry," says Simpson, his jaw tightening. "It's Tony Scott. Do you want to deal with this?" "You should deal with it," says Bruckheimer. "Why don't you talk to him?" "Jerry, I'm gonna go nuts on this," says Simpson. "Yeah, yeah, yeah," says his partner. "Well, you gotta do what you gotta do." There's an uneasy pause. Simpson gets up from behind his desk and takes the call in a side room. The producer, who admits he "probably has the most dramatic temper in the crowd," is not the kind of guy you want to go nuts on you. Born in Alaska, he hunted moose for dinner when he was seven years old. The two-minute conversation between director and producer ends when Simpson loudly lays down the law. "This is the last shot," he says. "You've got to promise me you're going to finish tonight!" Coming back into the main office, Simpson says, "That's it, Tony walked off the picture." A producer's joke. He decompresses, then explains the flare-up. "Tony is such a talented director that he always wants everything," Simpson says. "But the problem is everything won't fit the time frame. That's the constant dialectic." Filming for the new scene -- written by Towne over the last forty-eight hours -- is supposed to wrap by 1:00 a.m. No way. In the middle of the long night of shooting, Towne collapses on the sofa of a trailer parked outside the sound stage. Cruise stretches out on the floor. A couple of days later, Cruise chuckles over the time crunch, saying, "I got home about 4:30 in the morning. The rest of the week, I've been in the editing room, cutting, looping dialogue, then taking care of my office business at night." Pressure becomes Cruise. "It's exciting, because it really puts you absolutely to the limit," he says, his eyes fierce and focused. Simpson and Bruckheimer call him Laserhead. Tom cruise lives for Thunder. While the cast and crew joined the production last fall, he has been a man possessed ever since he stepped out of his car in Daytona Beach four years ago. That night, at the Olive Garden restaurant near the speedway, he noodled out his movie idea with Paul Newman, the Winston Cup racing-team owner J.R. "Rick" Hendrick, the ace driver Geoff Bodine and a handful of pit mechanics. Over dinner, the stock-car vets regaled the two actors with swashbuckling tales of maverick drivers and their hair-raising exploits. Cruise listened closely as Hendrick vividly described the maneuver known as "rubbin'," or "trading paint," in which cars bash into one another while smoking across the track at hundreds of miles an hour. Imagining close-ups of these gladiators jousting in their Chevrolet steeds, Cruise became even more convinced that he had found a great angle for an action picture. Everyone at the table knew Hollywood had never succeeded in making a classic stock-car story. Most of the attempts were cheesy comedies aimed at lowbrow audiences: Six Pack, with Kenny Rogers, Speedway, with Elvis Presley. Other films about elegant Formula One racing, like A1 Pacino's Bobby Deerfield, James Gamer's Grand Prix and Newman's own Winning, bristle with spectacular crashes but contain flat, tired characters running on empty. "I'd never seen a race-car picture that had really been done well," Cruise says. "A lot of them didn't have a story, just the action. As a result, you felt separated from the movie. I mean, I don't care how much machinery you have in a film. If I can't get involved with the characters, then for my money I'm not gonna enjoy it. I want the racing scenes to punctuate what's happening in the characters' lives." Cruise wrote a rough outline, weaving together fictional characters and Hendrick's racing anecdotes. He pitched the project to Ned Tanen, a Paramount exec and fellow car freak, and the studio recruited screenwriter Donald Stewart to flesh out the actor's treatment. When a less-than-visionary script came back, Tanen and Cruise called Simpson and Bruckheimer. In 1983, Simpson, a former production president at Paramount, had joined forces with his savvy producer friend, a former adman, to make the surprise smash Flashdance. Misfiring with the 1984 flop Thief of Hearts, the pair scored big with Beverly Hills Cop, Top Gun and Beverly Hills Cop II. The producers hired writer Warren Skaaren — who worked on Top Gun — to deliver a screenplay. Cruise immersed himself in Rain Man and Bom on the Fourth of July as Skaaren tore through seven drafts of a script. But the story still lacked substance. "There was frustration that the script wasn't getting there," says Cruise, who wanted the racing film to be released after his other two dramas. He kept in constant touch with Rick Hendrick, bringing him on the sets of Cruise's movies and flying to Hendrick's home base of Charlotte, North Carolina. Hendrick, a Southern racing-car magnate who also owns one of the country's largest auto dealerships, started to doubt that the film would ever get made, but he appreciated Cruise's determination. "Tom had been talkin' about this movie for years," he says. "You know, it's been like a dog with a bone — he has never let it alone." The script lingered in development hell. But a winter start date would be necessary for a lucrative summer 1990 release, so Bruckheimer and Simpson faced a daunting chore: convincing NASCAR to turn over its racetracks and facilities. "If we didn't get permission, we'd be fucked," says Simpson now. "We didn't have any backup plan, which is one of the ways we work that's not so wise." The producers had been through this routine before, when they hustled the navy into lending them F-14s for Top Gun before they had a script. But NASCAR wasn't the navy — it was a thriving private business that didn't have to recruit audiences. Simpson pitched Thunder as a first-class production: a PG-13-rated love story with real characters, not a corn-pone movie with hillbilly drivers and daffy bimbos at the pit stops. Then Simpson uttered the magic words: "We're going to take the image of stock-car racing as most of the public perceives it and turn it around. We're going to show them how high tech and professional it really is." When the producer was done, NASCAR president Bill France Jr. slowly leaned back in his chair and looked up at Simpson. "Son," said France in a husky Floridian drawl, "I've had the best salesmen come through here. I had Howard Hawks come in here and tell me about Red Line 7000 and what a terrific movie that was. And you know what, son? It was a piece of crap. But you're a helluva kid. I like your style. I'm gonna do it." Everyone shook hands and left smiling. The producers had NASCAR's commitment. They also got their director when Top Gun's Tony Scott joined the team after his own racing project fell through. Most of the elements were falling into place. Except for the script. Enter Robert Towne. Skaaren bailed out of the script from sheer exhaustion, and word spread that the job was up for grabs. An agent brought up Towne's name, and he seemed like a godsend. Arguably the most respected screenwriter in the business, Towne had salvaged troubled stories in the past. The gaunt, lanky writer made his bones as an uncredited script doctor on Bonnie and Clyde and The Godfather, then won an Oscar in his own right for writing Chinatown. Towne had approached Cruise for the lead in his latest project, Rush, about a Texas narcotics agent, but the actor said he wanted to do his racing film next. That's when Towne was asked to do a Thunder rewrite. He said he couldn't identify with elements in Skaaren's script but might consider starting from scratch. With Cruise as guide, Towne went to the races in Watkins Glen, New York. "He was hesitant," says Cruise. "He said he'd check it out, and I was trying not to put on too much pressure. But after a few hours, he came up to me smiling and said, 'I get it, Cruise. This is fantastic.'" Towne threw himself into his task. Wearing a small microphone on his cap, he could unobtrusively tape the recollections of drivers, grease monkeys, engine builders and sportscasters. Towne met with most of the great racing heroes. Men like Harry Gant, a former carpenter. And Dale Earnhardt, a.k.a. One Tough Customer for his aggressive rubbin' ability. Cruise and Towne were especially awed by a conversation with Richard Petty, the "king" of the stock-car world, who has won seven Daytona 500s. Petty has also survived several crashes, including a spectacular 1988 Daytona bang-up, when his car slammed into a wreck, hurled a barrier wall, rolled over and was finally T-boned by an oncoming vehicle. Petty talked to Cruise and Towne inside his trailer at Watkins Glen, just before a qualifying race. It was a casual conversation. Then Petty started discussing the crash. "He said it was almost in slow motion," says Cruise. "All he remembered was that he was looking at the ground, and it was lifting up. The way he told it was pretty powerful — that look in his eyes." Petty said his crash had temporarily blinded him, and Towne's imagination was sparked. "I became very interested in developing a story about a guy who had an accident where nothing physical happened to him, but he confronted subsequent problems that were a result of him having more talent than experience," he says. On Hendrick's suggestion, Towne talked to Harry Hyde, a crew chief and mentor to the late driver Tim Richmond, a controversial figure. Hyde keeps an icebox loaded with fruit-filled moonshine. His down-home personality and colorful life struck a chord with the writer. Towne decided to base his script on the relationships between a savvy team owner like Hendrick, a crusty crew chief like Hyde and a troubled driver like Richmond. People have compared Richmond to James Dean and other movie stars: a rebel with a car and designer clothes. "He wanted to be Don Johnson or Tom Cruise" was how one team sponsor described him. A well-known lady's man, Richmond died of AIDS last summer, possibly from a blood transfusion. Towne needed an angle for the love story, and Richmond's life provided that inspiration, too. He based his leading female character on an ophthalmologist Richmond had once loved. "There was something about a race-car driver getting his eyes examined that was appealing to me," says Towne. "In physically examining him, she looks into his eyes and into his psyche. She sees his fear on one side, and [his crew chief] sees it on the other." After a month of solid research, Towne had finally discovered the key to deciphering the movie's main character. He flew back to California and locked himself in his hilltop home in the Pacific Palisades, attacking the typewriter in a frantic bid to finish a first draft.

Meanwhile, the real Hendrick was hired on as a technical consultant. He and his employees readied a fleet of cars, including more than a dozen full-fledged racers costing over $100,000 each. "We built this car and put it on a vibrator, like a large dildo," says Scott. "We sent it blasting around the track on a flatbed trailer at 100 miles an hour with Cruise inside it. There were cameras outside, inside, underneath, all over the place." Engines mounted, cameras ready, casting well underway and Towne's first-draft script complete, the movie was rushed into production. After preliminary work in Phoenix last November, Thunder's crew flew to North Carolina for shooting at the Charlotte Motor Speedway. Before filming, Cruise took a drive in a test car, cranking up the rpm's. "I remember going through the corner, and it's a different world at that speed," he says. "It didn't seem fast, everything just seemed ... slow. The rear end kind of came out on me a little bit, and I caught it up. When you're squeezing on that throttle properly comin' off the fly and the car's just riding perfect — when that happens, you just feel like you can't do without that race car." Speedway president Humpy Wheeler was watching Cruise. As is his habit, Wheeler pulled out his stopwatch to time the car's speed. He couldn't believe his eyes: Cruise clocked in at 32.53 seconds per lap — 166 mph — a new track record for a noncertified NASCAR driver. Once filming began, the weather turned foul. Unexpected rainstorms and a freezing spell hit the city, making racing scenes difficult. After New Year's, the crew moved to Daytona, where half the picture would be shot over the next four months. The Thunder crew members worked long hours and lived the high life on their time off. There were lobster dinners, fully equipped gyms and private bashes. Thousands of college kids descended on the city for spring break, so there was always a party going on. Towne, however, didn't have much time to party. He was writing almost nonstop. Actors would get new script pages, sometimes just minutes before the camera rolled. Cruise came up with a novel solution: He taped pieces of his script onto the car's dashboard, so he could recite dialogue while zooming around the track. "I was driving and looking around all over, trying to read these lines I had just gotten," he says, flailing his arms and miming his frenetic movements. "And all of a sudden the car snaps out from the weight of the camera. I go, 'Oh, shit,' and go right up into the wall. "I put that thing into reverse," Cruise continues, "I'm cursing, and I take it around to the pits. If I had smashed the car and destroyed it, it would have cost us the afternoon, but we just dented the fender. Then what we started doing was having Bob Towne read me the dialogue through my radio earphone. He'd just read it over, I'd get a pace on it and read it back. It was fun. So in the movie, when it looks like my crew chief is talking to me and I'm listening intently, I was actually waiting for my next line."

While the "Star-Spangled Banner" boomed over loudspeakers before the first qualifying match, Cruise walked between two lanes of race cars with the wind rustling through his hair. Decked out in his black jumpsuit with neon trim and a Mello Yello logo emblazoned on his chest, he climbed into his number 51 stock car after the first heat concluded. Mechanics made last-minute adjustments on his Chevy Lumina, and a makeup man painted fake scratches on his cheek. Safety was a constant concern. A few accidents did occur on Thunder, none too serious. One driver hurt his ribs when a steering wheel disconnected from its mount in a speedy turn. And two crew members broke their arms after clowning around on a souped-up golf cart. Paramount's insurance policies restricted the actors from performing any business that was too risky. "They were very careful, but I did more stuff than just driving around the track," Cruise says. "I mean, I didn't do the crashes, obviously, but I had my share of stunts." The accident that nearly kills Cruise's character was among the final sequences shot in Daytona. Eleven cameras were set up to record the stunt. The flying flip-over crash required perfect timing. The driver had to get the car up to 125 mph down a straightaway, slide into a pool of water for the spin, then press a button igniting ten ounces of nitroglycerin tucked behind the rear axle. "The car did six barrel rolls, and at the end it was just this fucking shell," says Tony Scott. "The driver came out of the car yelling, 'Yeah!' with this enormous hard-on and giving everyone high fives. These stunt guys are crazy."

"Obviously, this kind of film is a bit different," he continues. "The amount of footage we have to go through can be tedious and excruciating. But when you've got people you trust, a lot of times the quick first decision is the best decision; it's kind of shooting from the hip, but it's also calculated. We always felt the pressure from the beginning, in August. It's been pedal to the floor from that point on." And it still is. Having gobbled down his breakfast, Cruise is due at Paramount in three minutes for a looping session. Curiously, he doesn't wear a watch and has to check with a waitress to make sure he's running on schedule. "Gotta go," he says, snatching the bill and heading for the parking lot, where he can hop on his Harley-Davidson and head back to work. "This is history in terms of what we're trying to accomplish in this time period. This isn't filmmaking, it's war." Источник | |

| Просмотров: 879 | Рейтинг: 0.0/0 |

| Всего комментариев: 0 | |

The making of a high-Cost, High-Risk summer Blockbuster

The making of a high-Cost, High-Risk summer Blockbuster